WORCESTERSHIRE has probably seen rather too much of the River Severn this winter than the locals have been comfortable with.

Severe floods have turned the surrounding land into huge lakes for weeks at a time, completely obscuring the line between river bank and meadow and often road as well.

So whether now is a good time to be bringing out a new book celebrating the myths, legends, history and magnificence of the UK’s longest river might be a moot point. But Worcester author Michael Dames has pushed the boat out and Spirits of the Severn (Austin Macauley) is on sale at £10.99.

This is not, by a long way, his first effort. For although he worked in education for much of his career, teaching art and history of art – in fact Michael was Rochdale’s Town Artist for a while - since 1976 he has undertaken a long term investigation into the mythology of the West of England, Wales and Ireland and become a full time writer. Spirits of the Severn is actually his ninth book.

In it he goes right back to the beginning and all the mysteries that surrounded water spurting from the ground when dinosaurs walked the Earth.

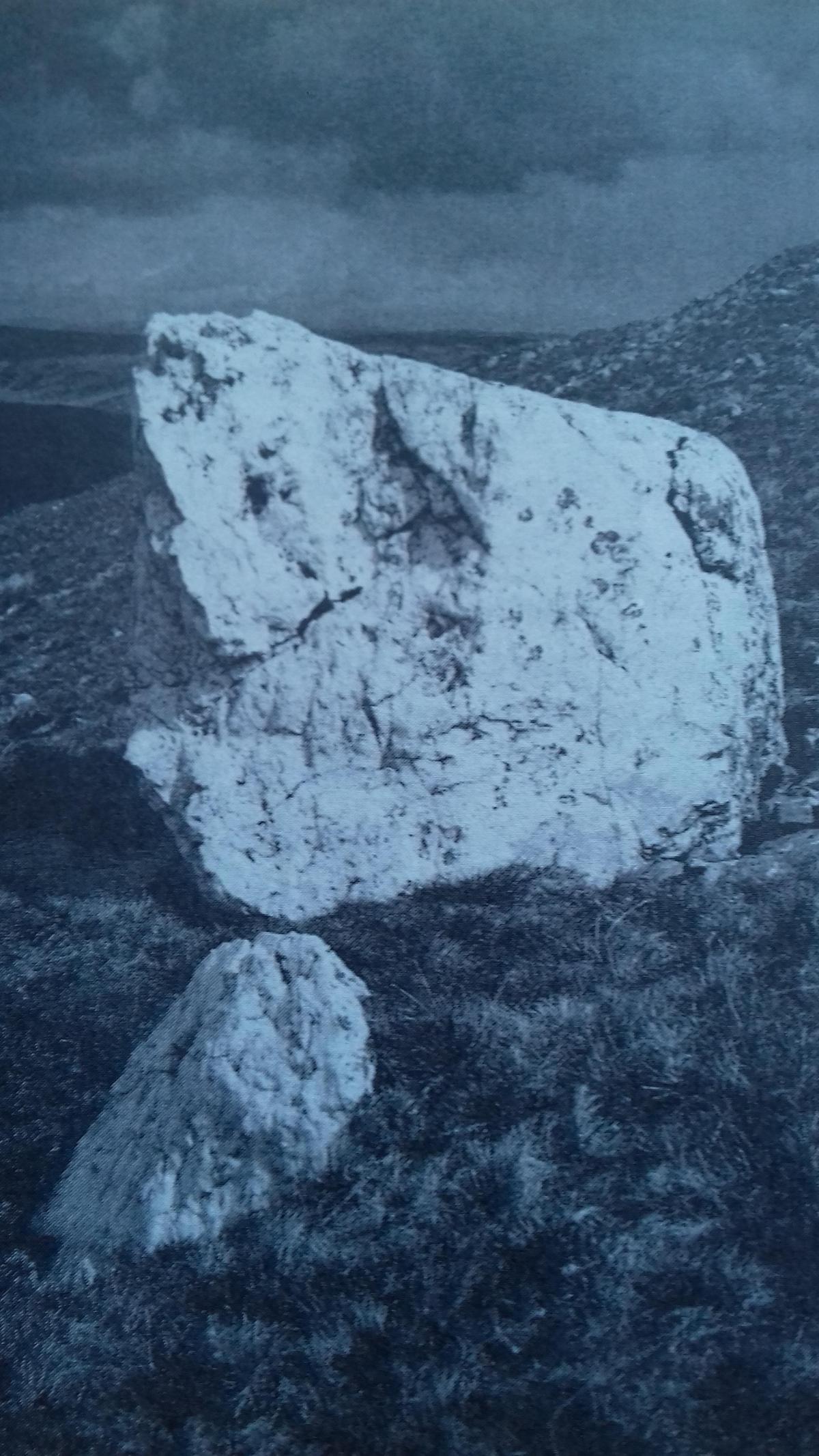

Michael writes “The 220 mile Severn rises at 2,000ft above the sea from beneath a ridge named in Welsh ‘Fuwch-wen-a-llo’, or the white cow and calf, after a pair of quartz-rich white rocks, deposited there by an ice sheet 14,000 years ago. Thanks to a deep fissure in her head, the white cow boulder seems to smile perpetually at her calf.” Which just goes to show the thought process they had in those pre-historic times, because today the most vivid imagination would struggle to draw that interpretation from a couple of quite average rocks, one large and one small. The ridge on which they lie is in the Pumlumon mountainous region of mid-Wales.

“Today a pair of two metre high poles stand close to that elusive source,” adds Michael. “They offer Welsh and English versions of the river’s name. Of these, the English term Severn emerged gradually during the Middle Ages from Sabrina via Saberna (c 76AD) to Saverne (c 1140AD) with Sabrina’s name becoming all but hidden, perhaps under Christian pressure in order to slough off her goddess persona.”

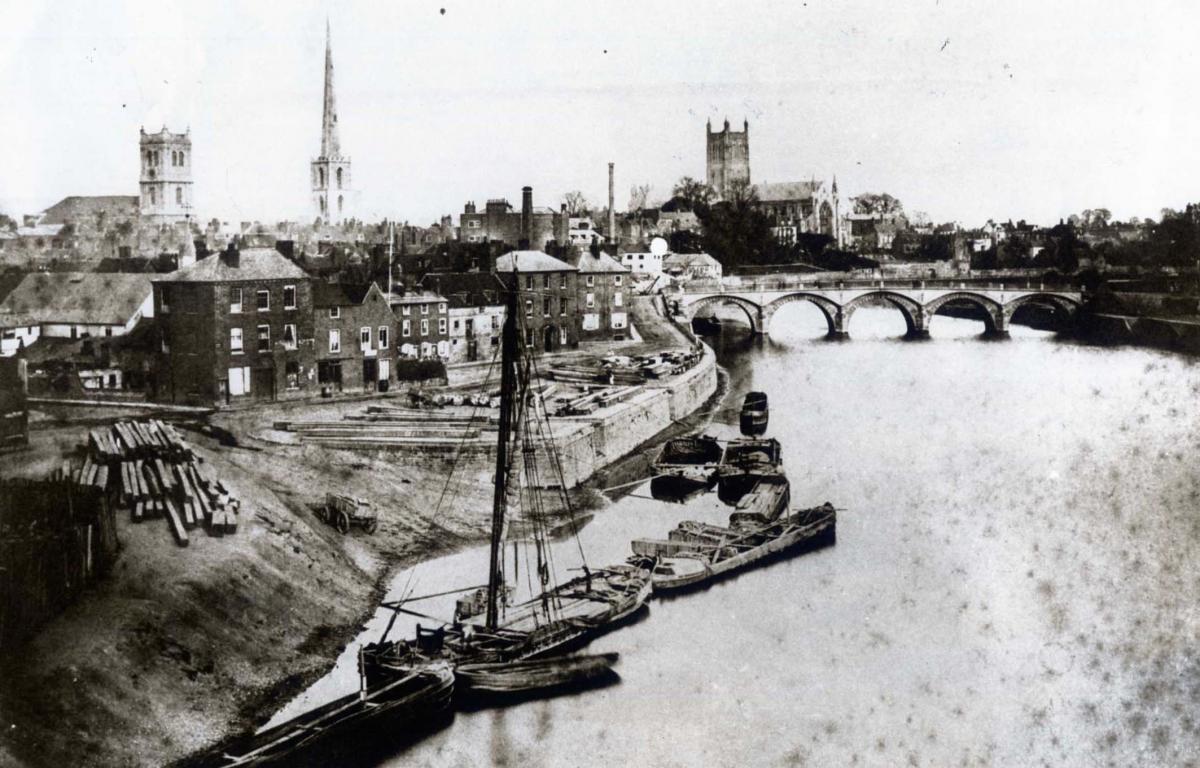

Despite it being regarded as one of the country’s mightiest rivers the Severn has historically flattered to deceive. A survey by engineer Thomas Telford in 1798 found it had an average depth of only 12-16 inches , which often dropped to only nine inches, and the waterway was only fully navigable for two months a year. Despite these problems, river traffic often reached as far upstream as Welshpool in Montgomeryshire.

Among the many hazards facing the barges carrying goods up and down the Severn were the Redstone Rapids, close to Stourport, the shoals of silt at Diglis, Worcester, and others difficulties at Holt and Lincombe.

In 1794, W Jessop recommended these could be eliminated by lock construction, which would give a reliable four feet of water, or narrowing the river would provide a reliable three feet depth. However, his ideas were rejected by Parliament and the trow men, who objected to the prospect of paying year round tolls to cover the cost of the work. They preferred to have their boats towed over the shallows when necessary.

After a failed bid In 1835 by the Severn Navigation Company, which aimed to build five locks and weirs between Gloucester and Stourport and provide 12ft of water to Worcester, enough for 300-ton barges, another company was formed by leading engineer Sir W Cubitt. This envisaged nine feet of water from Gloucester to Worcester via a series of locks and bridges at Worcester, Bewdley, Stourport and Upton. This time the plans got the green light and all the work was completed by 1859.

But Michael Dames’ book is not just a catalogue of river engineering. Like the floods, it covers much that happens or happened in the areas adjacent. Such as the annual cheese rolling at Cooper’s Hill, the legend of Twrch Trwyth, the giant boar which slew several of King Arthur’s knights, and the efforts of those with riverside cottages to keep the famous Severn Bore from their homes.

Britain’s longest natural waterway can be, by turns, both a beautiful and dangerous creature and as the author says: “It is unwise and irrational to forget the river’s silent power.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel